This December, the European Commission presented its new strategy to reduce its foreign dependence on critical raw materials. The objectives are ambitious, but achieving them is out of reach.

Rare earths and other critical materials, such as lithium and cobalt, are essential to many fields, from the automotive industry to renewable energy, technology and defence.

Essential for the new economy

With the energy transition and the digital revolution, the consumption of rare earths has exploded. Since 2015, it has grown by 13% annually.

Contrary to what their name suggests, rare earths are found in large quantities. However, significant volumes of raw rock must be extracted to obtain them.

They are also very unevenly distributed across the globe. Furthermore, the extraction and refining of rare earths are energy- and water-intensive processes that consume significant amounts of chemicals.

A market dominated by China

From the mid-1980s onwards, China, which has around 40% of the world's reserves, significantly increased its production.

Today, it accounts for the majority of extraction and, above all, 90% of refining, thanks to an aggressive policy of securing additional raw-material supplies from major emerging producers.

Chinese companies have also developed unrivalled expertise, making their production unbeatable in terms of price. This situation makes all the world's economies dependent on Beijing. This is particularly true of the European Union, where rare earth production is negligible.

A dangerous dependency

Whether it is cobalt or lithium for battery production, or rare-earth-based products such as magnets that are essential for manufacturing electric cars, wind turbines, and defence systems,

Europe is now almost entirely dependent on foreign countries for its supply of rare earths and critical materials.

This dependence has not been a problem for decades. But this is no longer the case in the current trade-war context. Controlling the production of essential rare earths is a powerful weapon that China does not hesitate to use.

To push Washington to reduce its tariffs on Chinese products, Beijing has restricted exports of certain rare earths and technological products that incorporate them.

As collateral victims of the Sino-American conflict, European companies were immediately penalised. Although the Chinese restrictions have since been suspended until November 2026 following a reduction in US tariffs, their introduction demonstrated Europe's significant vulnerability.

This is why the European Commission wants to accelerate its programme to secure its supplies.

Refining 40% of rare earth until 2030

The European Union has set itself an ambitious target for 2023. By 2030, it wants to produce 10% of its needs, refine 40%, recycle 25% and not depend on a single supplier for more than 65% of its needs, whereas most European manufacturers currently source all their supplies from China.

These targets were confirmed on 3 December during the presentation of a European plan called REsourceEU. To achieve them, the European Commission is focusing in particular on 47 strategic projects for the extraction, recycling and processing of metals.

The European Union also wants to establish strategic partnerships with countries outside China that produce rare earths, such as Australia, Canada and Chile. A European centre for critical raw materials will be created to make bulk purchases and store minerals.

European investment is not enough

All the decisions taken by the European Commission are a step in the right direction. However, it will be impossible to achieve the targets set.

Bureaucratic obstacles and strict environmental regulations hamper the projects. The most promising mining projects in Sweden will not be operational for another 10 years, according to the developers themselves.

In addition, the money allocated to these projects is also insufficient to compete with other economic powers. The European Commission plans to spend €3 billion over the next 12 months to strengthen the European Union's independence in critical materials.

By comparison, China, which wants to maintain its dominance in rare earths, invested $23 billion in the first half of 2025 to exploit Kazakhstan's mineral wealth alone.

As is often the case, the European Union has made the proper assessment and established the right strategy. But it is acting too late and with too few resources.

Investment opportunities

Demand for rare earths will continue to rise sharply in the coming years. However, it is a highly volatile market because the quantities traded are relatively small.

In 2024, cumulative global production of the 17 rare earths did not reach 400,000 tonnes, compared with more than 20 million tonnes for copper alone. The rise of a single deposit, a slight unexpected increase in demand or political decisions such as Chinese export restrictions can therefore cause prices to fluctuate significantly, both upwards and downwards.

Less risk-averse investors can nevertheless position themselves in this market via the VanEck Rare Earth and Strategic Metals ETF.

Among the stocks in our selection, Solvay is worth noting. The group owns the only plant outside China capable of refining all 17 rare earths on an industrial scale. Located in La Rochelle, it is set to become the epicentre of European production.

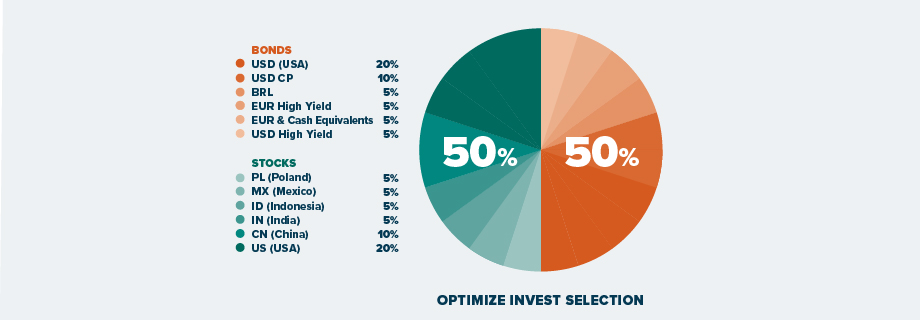

If you are interested in other investment opportunities, our suggested investment portfolio strategy may be helpful: